EXAMINING THE CONSEQUENCES OF LIVING IN A FOOD DESERT”

Since 1930, from homeownership to crime to trauma, Duval County Redlining has left a toll on its Most undesirable communities.”

The concept of “redlining” was a racist practice used mostly by government agencies to deny services, like mortgages, in majority Black inner-city neighborhoods. Outlawed through a series of laws in the latter half of the 20th century, redlining as a practice made Black homeownership difficult by targeting certain communities as being too risky to invest in. “If it was deemed to be a neighborhood where they did not want to encourage investment, it was considered hazardous and colored red on the map,” says Ennis Davis, Urban Planner at Modern Cities. “Essentially, across the U.S., not just Jacksonville, every majority-Black neighborhood in a city at that point in time became RED.”

[

Prior to the pandemic, 2.77 million Floridians were food insecure; 800,000 of those were children.

The Problem

The sad reality is that current new policies attempting to address the unintended consequences of REDLINING and RACIAL SEGREGATION have failed by the wayside since the draining of the swamp and her creeks. As a result, the after-effects of “food deserts” is now summed as a lack of “fresh fruits and vegetables”, unavailable at affordable prices in “the hood”, and the only alternative by local developers is more reliance on “corner stores” and your typical Safeway and Dollar General.

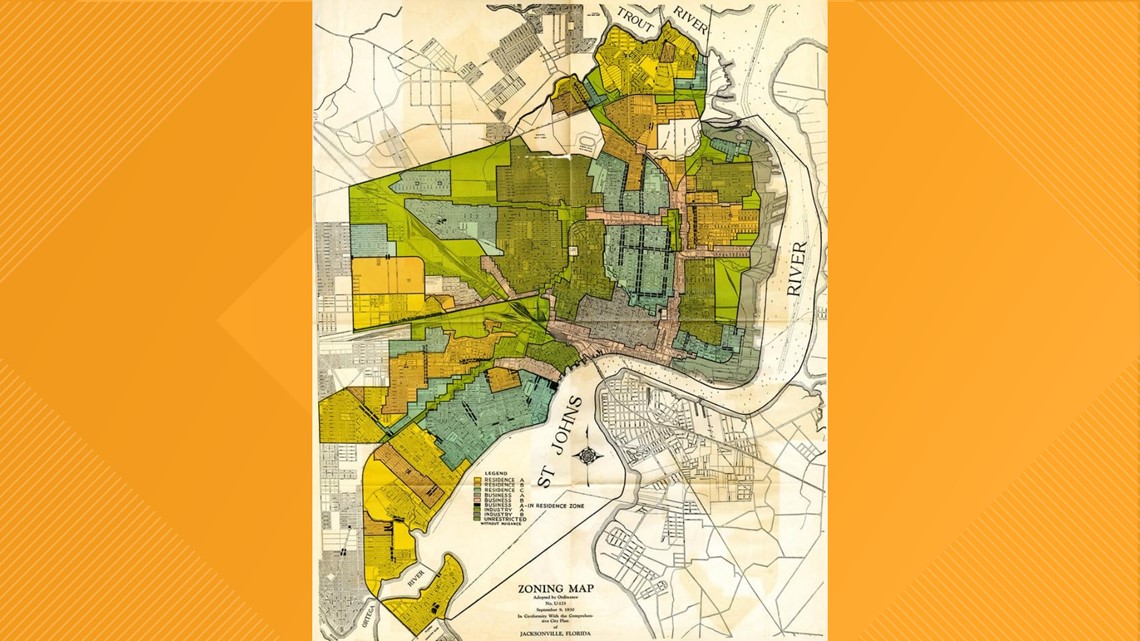

“There’s a reason that certain neighborhoods look like they look today. And that kind of set the foundation for what neighborhoods will be redlined in the following decades. On the map below, the dark green areas are zoned as “unrestricted.” states Mr. Davis in a recent interview with First Coast News.

Food deserts are a clear result of market forces being channeled through bad regulation. If the government wishes to change how people eat, it would be better off ending farm subsidies and inviting supermarkets into the cities. More generally, we as food consumers should recognize that what’s on the shelf is not just a product of poor consumer choices, but of poor government policies as well.

Finally, there is already an existing technological solution to the problem of availability: frozen and canned fruits and vegetables. These goods are high in nutritional content, and their packaging means that stores don’t have to worry about spoilage the way they do for their fresh produce. Fresh food has desirable qualities when it comes to taste and presentation, but it comes at a cost. Consumer demand decides whether a store carries fresh produce or not. Intervening in the market on aesthetic grounds is unlikely to create a good result for those who must actually live with the results.

Will you join us in preserving the principles of economic freedom and individual liberty for the rising generation?

Where do these subsidies come from? Meet America’s favorite barrel of pork, Farm Bill 2018. Whenever someone bemoans partisan gridlock, gently remind them that the farm bill always passes with bipartisan support and, in its 2018 iteration, has a price tag of over $1 trillion. For years the farm bill has heavily subsidized the production of wheat, corn, and soybeans with the intended consequence of lowering the prices of products containing those goods. Failing to provide access and opportunity to expand education of new crops such as industrial hemp, as we close out 2020, the situation looks memphis bleak for many who continue to live along Hogans Creek.

Another important issue affecting food availability in rural areas is population density. Those living in far-flung rural communities have to drive many miles to reach a supermarket. Supermarkets compete by offering a wide selection of goods at low prices. Without the population to generate a high turnover, they cannot justify their business model. Supermarkets, however, are not the only source of food services. In several prominent studies, stores with fewer than 20 employees were not counted. This methodology was employed because smaller stores, typically bodegas operating in ethnic neighborhoods, are less likely to have the space for fresh produce or refrigeration. This is a strong bias against smaller, family-owned businesses that operate in areas not traditionally covered by so-called big-box retailers.

Lack of population might explain the problem in rural areas, but regulation is the blight of the urban poor. Cities like New York and Washington, D.C., have made it very hard for companies like Walmart to operate in their cities. They have even passed discriminatory legislation with the express purpose of making it harder for Walmart to do business in those communities. The standard claim against Walmart is that its prices are so low that other businesses can’t compete. But if we’re trying to offer affordable produce to large numbers of people, isn’t that sort of the point? Cities that make it hard for big-box stores to operate hurt their poorest residents. Affluent suburbanites can afford to drive to (and purchase from) Whole Foods and other high-end grocers. For everyone else, zoning laws hurt those who lack the mobility to travel outside the zone or otherwise fail to meet the sticker price of these privileged establishments.

DID YOU KNOW?

It’s no surprise—at least for anyone who recalls from their principles of economics class that demand curves slope downward—that Americans’ consumption of carbohydrates has increased substantially over time. Indeed, we eat 25% more carbohydrates today as part of our daily diet than we did 30 years ago. All sweet treats and candy are cheaper because of corn subsidies, as are bread, cereals, crackers, and everything else containing wheat.

“END PRICE GAUGING”

Another issue here is not just access or low prices but relative prices. Low-income consumers have a choice of how to spend their food budget and obviously want the most nutritious caloric bang for their buck. Even if fruits and vegetables were available at lower prices, they must compete against heavily subsidized processed foods containing carbohydrates and corn syrup.

A USDA program of farmers’ markets and community gardens will do little to offset the literal billions spent on corn and wheat subsidies.